Before the arrival of European colonizers, East Africa was a vibrant tapestry of diverse indigenous societies and cultures, interconnected by complex trade networks that had flourished for centuries. This rich pre-colonial landscape laid the foundation for the region’s historical significance and continues to influence its cultural identity today.

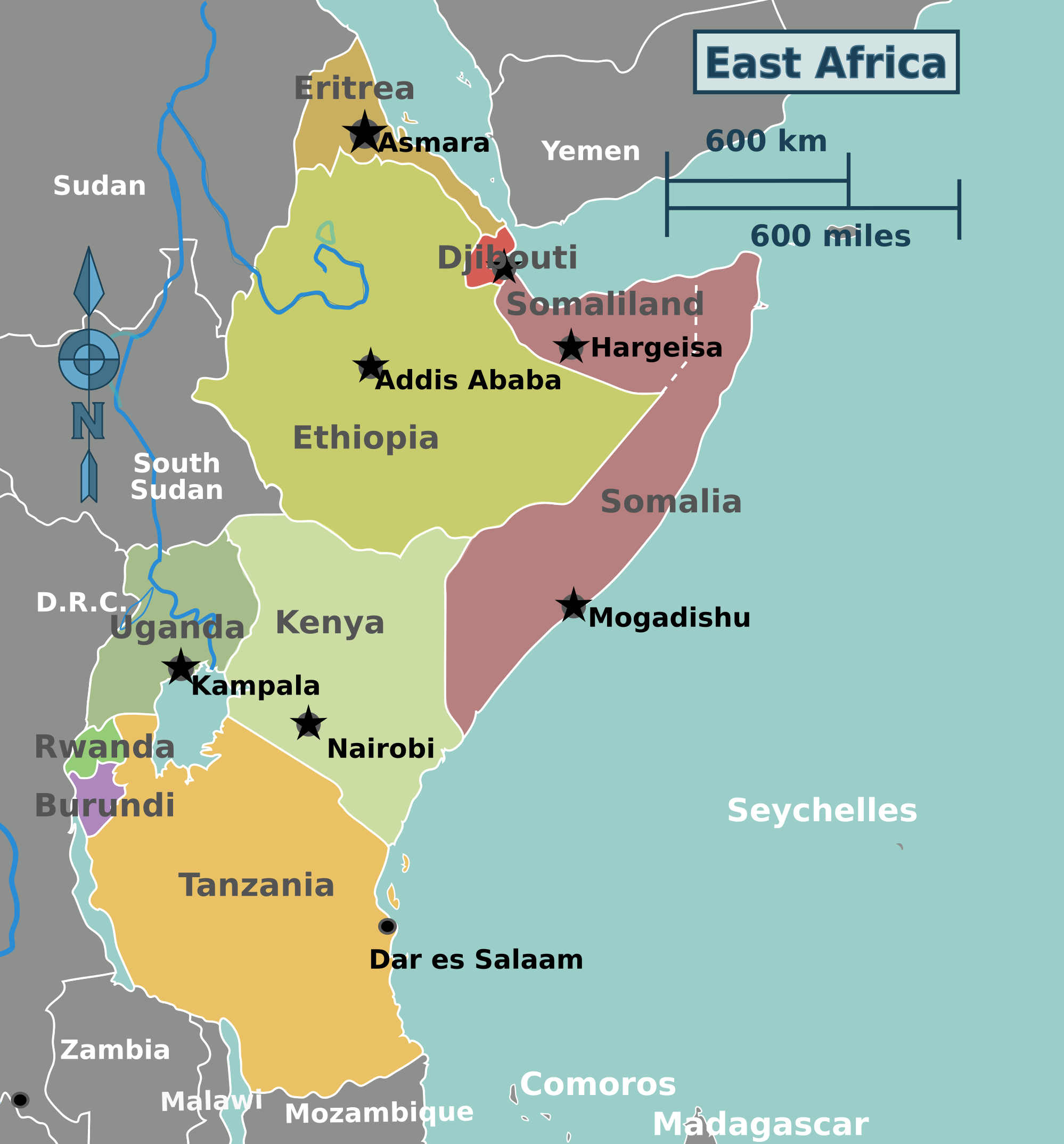

East Africa, encompassing modern-day Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and parts of Somalia and Ethiopia, was home to a multitude of ethnic groups, each with its own unique cultural practices, social structures, and political organizations. These societies ranged from small, egalitarian hunter-gatherer communities to large, centralized kingdoms.

One of the most prominent ethnic groups in the region was the Bantu-speaking peoples, who had migrated from West Africa over several centuries. They established agricultural societies and introduced iron-working technologies, significantly impacting the region’s development. The Kikuyu, Kamba, and Chagga are examples of Bantu groups that developed sophisticated farming techniques and social structures.

In the interlacustrine region around Lake Victoria, several powerful kingdoms emerged. The Buganda Kingdom, located in present-day Uganda, was particularly noteworthy for its complex political structure and cultural refinement. The Kabaka (king) ruled over a hierarchical system of chiefs and clans, maintaining a delicate balance of power. The Bunyoro and Ankole kingdoms also wielded significant influence in the area.

Along the coast, Swahili culture flourished, blending African, Arab, and Persian influences. City-states like Kilwa, Mombasa, and Zanzibar became centers of trade and Islamic learning. The Swahili language, a fusion of Bantu languages with Arabic and Persian loanwords, emerged as a lingua franca for trade and cultural exchange.

Pastoral societies, such as the Maasai, Samburu, and Turkana, developed unique cultures centered around cattle herding. These groups were known for their warrior traditions, intricate beadwork, and age-set systems that governed social organization.

In the Horn of Africa, the Kingdom of Aksum (in present-day Ethiopia and Eritrea) had already established a rich legacy of Christianity and literacy. The sophisticated Aksumite civilization left behind impressive monuments and a written script, Ge’ez, which is still used in Ethiopian Orthodox Christian liturgy.

Existing Trade Networks

Long before European intervention, East Africa was integrated into vast trade networks that connected the interior with the coast and linked the region to the wider Indian Ocean world. These networks facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices, contributing to the region’s diversity and economic vitality.

The Indian Ocean trade, which had existed for millennia, reached its zenith during this period. Swahili city-states along the coast acted as crucial intermediaries between the African interior and overseas traders from Arabia, Persia, India, and even China. Goods such as gold, ivory, animal hides, and slaves were exported, while cloth, beads, porcelain, and metal goods were imported.

The trade in ivory was particularly lucrative, with elephant tusks highly prized in markets across Asia and Europe. This trade led to the establishment of caravan routes that penetrated deep into the interior, connecting coastal merchants with inland societies.

Salt, an essential commodity for preservation and flavor, was another key trade item. The salt trade created networks between the coast, where it was produced through evaporation of seawater, and inland areas where it was scarce.

In the interlacustrine region, local trade networks developed around Lake Victoria and other Great Lakes. These facilitated the exchange of agricultural products, iron goods, and other locally produced items between different ethnic groups and kingdoms.

The long-distance trade routes also served as conduits for the spread of Islam into the interior. Muslim traders, settling in trading posts and marrying into local communities, gradually introduced Islamic practices and beliefs, particularly in urban centers.

In the northern parts of East Africa, trade routes connected the region with the Nile Valley and the Red Sea, linking it to the Mediterranean world. The Kingdom of Aksum, for instance, had long-standing trade relations with the Byzantine Empire and various Arab states.

The pre-colonial societies and trade networks of East Africa laid a crucial foundation for the region’s future development. The diversity of cultures and political systems would later influence resistance to colonialism and shape post-independence nation-building efforts.

The Swahili language and culture, products of centuries of coastal trade and cultural mixing, continue to play a significant role in modern East Africa. Swahili serves as an official or national language in several countries and remains an important lingua franca.

Traditional social structures and cultural practices, though altered by colonialism and modernization, still inform many aspects of East African life. Age-set systems, for instance, continue to play a role in some communities, while traditional forms of conflict resolution and governance have been incorporated into modern political systems in some areas.

The legacy of pre-colonial trade networks can be seen in modern East African economic integration efforts, such as the East African Community. These initiatives often draw inspiration from the region’s long history of cross-border commerce and cultural exchange.

Understanding pre-colonial East Africa is crucial for appreciating the depth and complexity of the region’s history. It challenges simplistic narratives that begin with European colonization and highlights the agency and achievements of African societies. As East Africa continues to evolve in the 21st century, this rich pre-colonial heritage remains an essential part of its identity and a source of cultural pride.

Colonization

The colonization of East Africa by European powers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was driven by a complex interplay of economic interests, strategic considerations, and the broader context of the Scramble for Africa. Understanding these motivations is crucial for grasping the full scope of the colonial enterprise and its lasting impact on the region.

Perhaps the most significant driving force behind European colonization of East Africa was the pursuit of economic gain. As industrialization accelerated in Europe, there was an increasing demand for raw materials to fuel factories and new markets to sell manufactured goods.

East Africa offered a wealth of natural resources that were highly coveted by European powers. Ivory, for instance, was in great demand for luxury goods such as piano keys and billiard balls. The region’s potential for producing cash crops like cotton, sisal, and coffee was also recognized early on. Additionally, there were hopes of finding mineral wealth, particularly gold, which had already been discovered in other parts of Africa.

The colonial powers also saw East Africa as a potential market for their manufactured goods. By establishing control over the region, they could create captive markets for their products, often at the expense of local industries and craftsmen.

Furthermore, the abolition of the slave trade in the early 19th century had led many European nations to seek alternative forms of labor and economic exploitation. This resulted in the concept of “legitimate commerce,” which aimed to replace slave trading with other forms of trade. However, this often led to equally exploitative economic relationships between Europeans and Africans.

The construction of the Suez Canal in 1869 significantly increased the strategic and economic importance of East Africa. The canal shortened the sea route between Europe and Asia, making control of the East African coast and the Red Sea crucial for maritime trade.

Beyond economic considerations, East Africa held significant strategic importance for European powers. Control over this region could provide valuable naval bases, safeguard trade routes, and serve as a foothold for further expansion into the African interior.

The British, in particular, viewed East Africa as critical to securing their interests in India, their most prized colonial possession. By controlling territory in East Africa, they could protect the sea routes to India and strengthen their overall imperial position. The port of Mombasa, for instance, became a crucial coaling station for British ships traveling to and from India.

For other European powers, such as Germany and Italy, colonizing parts of East Africa was seen as a way to elevate their international status and compete with established colonial powers like Britain and France. This was particularly important for newly unified nations like Germany and Italy, which were eager to assert themselves on the global stage.

The source of the Nile, long a mystery to Europeans, was another strategic consideration. Control over the Nile’s headwaters could potentially give a colonial power leverage over Egypt, which depended entirely on the river for its agriculture and economy.

Moreover, some European strategists saw East Africa as a potential buffer zone against the expansion of rival powers or the spread of Islam from the north. This defensive mindset played a role in shaping colonial boundaries and policies.

The colonization of East Africa cannot be fully understood without considering the broader context of the Scramble for Africa. This period, roughly from 1881 to 1914, saw European powers rapidly carving up the African continent among themselves.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, while not directly causing the Scramble, provided a framework for European colonial expansion in Africa. It established the principle of “effective occupation,” which meant that European claims to African territory had to be backed up by actual presence and administration on the ground. This led to a race among European powers to establish control over as much territory as possible, often with little regard for existing African political entities or ethnic boundaries.

In East Africa, this scramble manifested in the competition between Britain and Germany to establish spheres of influence. The two powers eventually agreed on a division of territory, with Britain taking what would become Kenya and Uganda, while Germany claimed what is now mainland Tanzania.

The Scramble was fueled by a mix of national pride, imperial ambition, and a genuine belief among many Europeans that they had a civilizing mission in Africa. This notion of the “white man’s burden” – the idea that European nations had a duty to bring civilization and Christianity to “backward” peoples – provided a moral justification for colonial expansion.

Moreover, advances in technology played a crucial role in enabling the Scramble. Innovations such as the steamship, the railway, and quinine (which helped combat malaria) made it possible for Europeans to penetrate deeper into the African interior and establish more effective control.

The rapid pace of the Scramble often led to hasty and arbitrary decision-making. Borders were frequently drawn with little consideration for local realities, leading to the division of ethnic groups and the creation of artificial boundaries that continue to cause conflicts in modern Africa.

The motivations behind the colonization of East Africa were multifaceted and interconnected. Economic interests, ranging from the desire for raw materials to the search for new markets, played a central role. Strategic considerations, including the control of trade routes and the establishment of imperial footholds, were equally important. All of this took place within the context of the Scramble for Africa, a period of intense competition among European powers.

Understanding these motivations is crucial for comprehending the nature of colonial rule in East Africa and its long-lasting impacts. The economic exploitation, strategic calculations, and arbitrary borders that resulted from this period continue to shape the region’s politics, economy, and society to this day. By examining these historical drivers, we can better understand the complexities of East Africa’s colonial legacy and the challenges faced by post-colonial nations in the region.

Colonial Powers and Their Territories in East Africa: Shaping the Region’s Modern Borders

The colonization of East Africa by European powers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries led to the establishment of distinct colonial territories that would eventually form the basis for modern nation-states in the region. The primary colonial powers in East Africa were Britain, Germany, and Italy, each carving out their own spheres of influence and leaving lasting legacies that continue to shape the region today.

British East Africa

British East Africa was the largest and most influential of the colonial territories in the region. It encompassed what are now the modern nations of Kenya and Uganda, as well as parts of present-day Tanzania (namely, Zanzibar and Pemba).

The British presence in East Africa began with the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC), chartered in 1888 to administer the region on behalf of the British government. However, faced with financial difficulties and the challenges of administering such a vast territory, the IBEAC transferred its rights to the British government in 1895, leading to the formal establishment of the East Africa Protectorate.

Kenya, the centerpiece of British East Africa, was valued for its strategic location, agricultural potential, and as a gateway to Uganda. The British constructed the Uganda Railway, nicknamed the “Lunatic Express,” from Mombasa to Lake Victoria between 1896 and 1901. This massive infrastructure project not only facilitated the movement of goods and administration but also opened up the interior for white settlement, particularly in the fertile highlands.

In Uganda, the British established a system of indirect rule, working through existing kingdoms and chiefdoms, particularly the powerful Buganda Kingdom. This approach, while preserving some traditional power structures, also exacerbated ethnic divisions that would have long-lasting consequences.

Zanzibar, which had been a British protectorate since 1890, was integrated into British East Africa in 1963, shortly before independence. The island’s history as a major trading hub and center of Swahili culture added a unique dimension to British colonial holdings in the region.

British administration in East Africa was characterized by policies such as land alienation for white settlers (particularly in Kenya), the introduction of cash crops, and the implementation of racial segregation. These policies would significantly shape the social, economic, and political landscape of the region, leading to tensions that would eventually fuel independence movements.

German East Africa

German East Africa, corresponding roughly to modern-day mainland Tanzania, Burundi, and Rwanda, was established in the 1880s as Germany sought to assert itself as a colonial power.

The territory was initially administered by the German East Africa Company, but following the Abushiri Revolt of 1888-1889, the German government took direct control. The Germans faced significant resistance, most notably in the Maji Maji Rebellion of 1905-1907, which was brutally suppressed.

German colonial policy in East Africa differed somewhat from that of the British. While there was some white settlement, it was not as extensive as in British territories. The Germans focused more on plantation agriculture, developing crops such as sisal, which remains an important export for Tanzania today.

The Germans also invested heavily in infrastructure, constructing railways and improving ports. Dar es Salaam, which became the capital of German East Africa, was developed into a major urban center and remains Tanzania’s largest city and economic hub.

In terms of administration, the Germans generally favored a more direct form of rule compared to the British system of indirect rule. This approach involved dismantling many traditional power structures and implementing a more centralized system of governance.

German rule in East Africa came to an end with World War I. Following Germany’s defeat, its East African territory was divided between Britain and Belgium under League of Nations mandates, with Britain taking control of Tanganyika (mainland Tanzania).

Italian East Africa

Italian colonial ambitions in East Africa were primarily focused on the Horn of Africa, encompassing present-day Eritrea, Somalia, and parts of Ethiopia. While geographically distinct from British and German East Africa, Italian activities in the region played a significant role in the colonial landscape of greater East Africa.

Italy established its first foothold in the region with the colonization of Eritrea in 1890. In 1936, following the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, Italy annexed Ethiopia, combining it with Eritrea and Italian Somaliland to form Italian East Africa.

However, Italian control over this vast territory was short-lived. During World War II, Allied forces, including troops from other African colonies, drove the Italians out. By 1941, Italian East Africa had effectively ceased to exist, with Ethiopia regaining its independence and Eritrea coming under British administration.

Despite its relatively brief existence, Italian colonialism left its mark on the region. In Eritrea, for instance, Italian influence can still be seen in architecture, cuisine, and certain cultural practices. The legacy of Italian rule also played a role in shaping the distinct identity that would later fuel Eritrea’s push for independence from Ethiopia.

The division of East Africa among these colonial powers had profound and lasting impacts on the region:

- Borders: The boundaries drawn by colonial powers often disregarded ethnic and cultural realities on the ground, leading to the division of communities and the creation of artificial nation-states. These colonial borders, largely maintained after independence, continue to be a source of tension in some areas.

- Administrative systems: Each colonial power implemented its own administrative structures, legal systems, and educational policies. These differences are still reflected in the governance systems of modern East African nations.

- Economic development: Colonial economic policies, focused on resource extraction and cash crop production, shaped the economic structures of these territories in ways that continue to influence their development trajectories today.

- Language and culture: The languages of the colonial powers – English, German, and Italian – became lingua francas in their respective territories, influencing education, administration, and in some cases, national identity.

- Regional dynamics: The different colonial experiences of each territory contributed to divergent paths of development and different approaches to post-colonial nation-building.

Methods of Colonization in East Africa: From Treaties to Administration

The colonization of East Africa by European powers was not a uniform process, but rather a complex interplay of diplomatic maneuvering, military force, and administrative implementation. The methods employed varied depending on the colonial power, the specific region, and the level of resistance encountered. Understanding these methods provides crucial insight into how European nations established and maintained control over vast territories in East Africa.

Treaties and Agreements

One of the primary methods used by European powers to establish their presence in East Africa was through treaties and agreements with local rulers. This approach was often the first step in the colonization process, as it provided a veneer of legitimacy to European claims and could sometimes avoid immediate conflict.

The British, in particular, were adept at using treaties to expand their influence. For example, the Imperial British East Africa Company signed numerous agreements with local chiefs and rulers, ostensibly for protection and trade rights. These treaties often included clauses that were not fully understood by the African signatories, granting extensive rights to the British.

Perhaps the most famous of these agreements was the Buganda Agreement of 1900, signed between the British and the Kingdom of Buganda in present-day Uganda. This treaty formalized British protection over Buganda and laid the groundwork for indirect rule in the region. While it preserved some autonomy for the Buganda Kingdom, it effectively brought the powerful state under British control.

Similarly, the Germans used treaties to establish their presence in what would become German East Africa. Carl Peters, representing German interests, signed a series of treaties with local chiefs in 1884-1885, which became the basis for German claims in the region.

However, these treaties were often problematic. Many African leaders did not fully understand the implications of what they were signing, given language barriers and different cultural concepts of land ownership and sovereignty. Europeans often took advantage of this misunderstanding to claim much broader rights than were intended by the African signatories.

Military Conquest

While treaties and agreements were preferred for their lower cost and potential for peaceful transition, European powers were not hesitant to use military force when deemed necessary. Military conquest was employed when treaties were rejected, when local resistance emerged, or when competing European powers threatened territorial claims.

The British, for instance, engaged in numerous military campaigns to subdue resistant communities in Kenya. The Nandi Resistance (1895-1906) is a notable example, where British forces fought a prolonged war against the Nandi people who opposed colonial intrusion into their lands.

In German East Africa, the Maji Maji Rebellion of 1905-1907 led to a brutal military response. The Germans crushed the uprising with overwhelming force, resulting in devastating casualties among the local population and cementing German control over the territory.

Italian attempts to colonize Ethiopia provide another example of military conquest, albeit an unsuccessful one initially. In 1896, Italy invaded Ethiopia but was decisively defeated at the Battle of Adwa, allowing Ethiopia to maintain its independence until the Second Italo-Ethiopian War in 1935.

Military conquest often involved technological superiority on the part of the Europeans, who possessed advanced weapons like machine guns. This technological edge, combined with tactics developed in other colonial theaters, allowed relatively small European forces to overcome larger African armies.

Establishment of Administrative Systems

Once control was established, whether through treaties or conquest, the colonial powers set about creating administrative systems to govern their new territories. These systems were designed to maintain order, extract resources, and implement colonial policies.

The British largely favored a system of indirect rule, particularly in areas with strong existing political structures. This approach involved governing through traditional leaders, who were given authority over local affairs but remained subordinate to British officials. This system was prominently used in Uganda, where the Buganda Kingdom and other traditional polities were incorporated into the colonial administration.

In Kenya, however, the British implemented a more direct form of rule, especially in areas designated for white settlement. This involved creating new administrative units, appointing British officials, and often disregarding or dismantling traditional African governance structures.

The Germans, in their East African territories, generally preferred a more direct approach to colonial administration. They established a centralized bureaucracy, divided the territory into districts headed by German officials, and often sidelined traditional leaders.

A key aspect of colonial administration was the implementation of new legal systems. European laws were introduced, often superseding or modifying traditional African legal practices. These new legal frameworks were crucial in enforcing colonial rule, regulating trade, and managing land ownership – often to the disadvantage of the indigenous population.

Education systems were also established, primarily to train a limited number of Africans for lower-level positions in the colonial administration. These schools, often run by Christian missionaries, played a significant role in spreading European languages and cultural values.

The colonial powers also implemented economic systems designed to benefit the metropole. This included the introduction of cash crops, the development of extractive industries, and the creation of transportation infrastructure like railways and ports to facilitate the export of goods.

Taxation was another crucial aspect of colonial administration. Various forms of taxes were imposed on the African population, often forcing them into wage labor to earn money to pay these taxes. This system helped to create a labor force for European enterprises and to fund the colonial government.

The legacies of these colonization methods continue to influence East Africa today. The borders drawn during this period largely define modern nation-states. Administrative structures, legal systems, and educational institutions established under colonial rule often formed the basis for post-independence governance. Understanding these methods of colonization is crucial for comprehending the historical context of contemporary East African politics, economics, and society.

The Impact of Colonization on East Africa

The colonization of East Africa by European powers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought about sweeping changes that fundamentally altered the political, economic, and social fabric of the region. These impacts continue to shape East African societies today, influencing everything from governance structures to cultural practices.

The imposition of colonial rule led to dramatic political changes across East Africa. Traditional systems of governance, which had evolved over centuries, were either dismantled or significantly altered to serve colonial interests.

In areas where indirect rule was implemented, such as Uganda, existing political structures were often co-opted into the colonial administration. While this allowed some traditional leaders to maintain a degree of authority, it also fundamentally changed the nature of their power. These leaders became accountable to colonial administrators rather than to their people, altering traditional checks and balances.

In other areas, particularly where direct rule was imposed, new political structures were created that often disregarded existing ethnic and cultural boundaries. The drawing of colonial borders divided some ethnic groups across different territories while forcing others into artificial political unions. This redrawing of the political map laid the foundation for many of the border disputes and ethnic tensions that persist in the region today.

The introduction of European-style bureaucratic systems also had a lasting impact. New administrative divisions were created, and a class of African civil servants began to emerge. While initially serving colonial interests, this educated elite would later play a crucial role in independence movements and post-colonial governance.

Moreover, the colonial period saw the introduction of new legal systems based on European models. These systems often existed in parallel with traditional legal practices, creating a dual legal structure that many East African countries still grapple with today.

Perhaps the most significant and lasting impact of colonization was the fundamental restructuring of East African economies to serve European interests. The colonial powers implemented systems designed to extract resources and generate profits for the metropole, often at the expense of local development.

One of the key features of this economic transformation was the introduction of cash crops. Crops like coffee, tea, sisal, and cotton were introduced or expanded for export. While this created new economic opportunities for some, it also led to the neglect of food crops and traditional agricultural practices, increasing vulnerability to famine and economic fluctuations.

The colonial powers also implemented systems of land alienation, particularly in areas designated for European settlement. In Kenya, for instance, the fertile highlands were reserved for white settlers, displacing many African communities from their ancestral lands. This dispossession would later fuel anti-colonial sentiments and remains a contentious issue in post-colonial land politics.

Forced labor was another feature of colonial economic exploitation. Various systems, including taxation and legal coercion, were used to create a pool of cheap labor for European enterprises. This not only disrupted traditional economic activities but also led to significant social dislocation as men were often forced to leave their communities to seek work.

The development of infrastructure, such as railways and ports, while ostensibly for development, was primarily designed to facilitate the export of raw materials and the import of manufactured goods. This export-oriented infrastructure continues to shape East African economies today, often at the expense of regional integration and internal market development.

The social and cultural impact of colonization on East African societies was profound and multifaceted. Colonial policies and practices led to significant changes in social structures, cultural practices, and individual identities.

Education was a key tool of cultural transformation. Colonial schools, often run by Christian missionaries, introduced European languages, values, and knowledge systems. While this education provided opportunities for some Africans, it also led to the marginalization of indigenous knowledge and languages. The emphasis on European languages, particularly English, as the language of administration and education continues to influence language policies and social mobility in East Africa today.

Christianity spread rapidly during the colonial period, often at the expense of traditional religious practices. While many East Africans embraced Christianity, this religious shift also led to the erosion of certain cultural practices and beliefs tied to traditional spirituality.

Urbanization accelerated under colonial rule as new administrative centers were established and economic activities concentrated in certain areas. This led to the growth of cities like Nairobi, Dar es Salaam, and Kampala, creating new social dynamics and urban cultures distinct from rural traditions.

The colonial period also saw significant demographic changes. The introduction of Western medicine led to population growth, while forced labor and economic policies resulted in new patterns of migration. These shifts altered traditional social structures and community dynamics.

Gender roles and family structures were also impacted. Colonial policies often favored men in education and employment, reinforcing and sometimes exacerbating existing gender inequalities. The introduction of European concepts of marriage and family sometimes clashed with traditional practices, leading to changes in family structures and inheritance patterns.

The arbitrary drawing of colonial borders divided many ethnic groups while forcing others into new political entities. This redrawing of the cultural map of East Africa has had lasting implications for ethnic identities and inter-group relations, often contributing to post-colonial conflicts.

The legacy of these colonial impacts is evident in ongoing debates about governance, economic development, language policy, and cultural identity across East Africa. Understanding this colonial legacy is crucial for comprehending contemporary East African societies and the challenges they face in the post-colonial era. As East African nations continue to navigate their place in the global community, they do so against the backdrop of this complex colonial history, seeking to forge paths that balance historical legacies with contemporary aspirations.

Resistance to Colonization in East Africa

The colonization of East Africa was not a process of passive acceptance by the indigenous populations. Throughout the colonial period, East Africans engaged in various forms of resistance against European domination. This resistance ranged from large-scale armed rebellions to more subtle forms of cultural and social resistance. Understanding these acts of defiance is crucial for appreciating the agency of East African peoples in the face of colonial oppression and for comprehending the roots of nationalist movements that would eventually lead to independence.

Uprisings and Rebellions

Armed resistance against colonial rule took many forms across East Africa, from localized revolts to region-wide uprisings. These rebellions, while ultimately suppressed by superior European military technology, significantly challenged colonial authority and laid the groundwork for future resistance movements.

One of the most significant early rebellions was the Abushiri Revolt (1888-1889) in German East Africa. Led by Abushiri ibn Salim al-Harthi, this uprising united coastal Arabs and Swahili people against German colonial expansion. Although ultimately defeated, the revolt forced the German government to take direct control of the territory from the German East Africa Company, reshaping the nature of German colonialism in the region.

The Maji Maji Rebellion (1905-1907) in German East Africa was another major uprising. Spanning a vast territory in what is now southern Tanzania, this rebellion united various ethnic groups against German colonial rule. The rebellion was fueled by a belief in the protective power of sacred water (maji) that was supposed to turn German bullets into water. Despite initial successes, the rebellion was brutally suppressed, resulting in devastating famine and loss of life. However, it significantly weakened German control and is remembered as a key moment in the development of Tanzanian national identity.

In British East Africa, the Nandi Resistance (1895-1906) stands out as one of the most prolonged and effective challenges to colonial rule. The Nandi people of western Kenya fiercely resisted British encroachment for over a decade, employing guerrilla tactics that frustrated colonial forces. The eventual defeat of the Nandi came at a high cost to the British and demonstrated the determination of African peoples to defend their lands and way of life.

The Giriama Uprising (1913-1914) in coastal Kenya is another example of armed resistance against British rule. Led by the prophetess Mekatilili wa Menza, this rebellion was sparked by British attempts to recruit Giriama men for World War I. Although short-lived, the uprising significantly disrupted British control in the coastal region and is celebrated today as an early example of women’s leadership in anti-colonial struggles.

In Uganda, the Lamogi Rebellion (1911-1912) saw the Acholi people resist British attempts to disarm them and impose hut taxes. This rebellion, while ultimately unsuccessful, demonstrated the widespread discontent with colonial policies across different regions of East Africa.

Passive Resistance and Cultural Preservation

While armed rebellions captured headlines and demanded immediate colonial response, more subtle forms of resistance played a crucial role in challenging colonial authority and preserving indigenous cultures.

One form of passive resistance was non-compliance with colonial demands. This could take the form of tax evasion, refusal to engage in forced labor, or deliberate slowdowns in work. These actions, while often individual or small-scale, collectively posed significant challenges to the effective functioning of colonial economies and administrations.

Cultural preservation was another critical form of resistance. Many East African communities worked to maintain their traditional practices, languages, and belief systems in the face of European attempts at cultural domination. This often involved adapting traditional practices to new conditions or blending them with introduced elements in ways that preserved core cultural values.

Religious movements often served as vehicles for both spiritual and political resistance. For example, the Dini ya Msambwa movement in western Kenya, founded by Elijah Masinde in the 1940s, combined traditional religious elements with anti-colonial messages. Similarly, independent African churches, which blended Christianity with indigenous spiritual practices, often became centers of cultural resistance and preservation.

Education became another battleground for resistance. While colonial schools were tools for spreading European culture, they also inadvertently provided Africans with tools to challenge colonial rule. Many educated Africans used their knowledge to articulate grievances against colonialism and to organize resistance. Additionally, informal education systems emerged to preserve and transmit traditional knowledge and values.

The preservation and adaptation of indigenous languages was a crucial form of cultural resistance. Despite the imposition of European languages in administration and formal education, many East African communities maintained their languages as a way of preserving their identity and resisting cultural assimilation.

In the economic sphere, the continuation of traditional economic practices alongside imposed colonial systems was a form of resistance. Barter systems, communal labor practices, and traditional craft production persisted, providing alternatives to full integration into the colonial economy.

The arts became another avenue for resistance and cultural preservation. Traditional music, dance, and storytelling often incorporated themes of resistance or served to maintain historical memories of pre-colonial times. These artistic expressions helped to foster a sense of shared identity and resistance among colonized peoples.

Women often played crucial roles in passive resistance and cultural preservation. In many societies, women were the primary custodians of traditional knowledge and practices. Their roles in childrearing, food production, and community organization allowed them to pass on cultural values and resist colonial impositions in daily life.

While major rebellions often ended in defeat due to the superior military technology of the colonial powers, they significantly weakened colonial control and laid the groundwork for future resistance. Moreover, these uprisings live on in collective memory as powerful symbols of African courage and determination.

The less visible forms of passive resistance and cultural preservation were equally important. By maintaining their cultures, languages, and traditional practices, East African peoples ensured that colonization never achieved total domination. These acts of everyday resistance helped to maintain a sense of identity and dignity that would fuel later nationalist movements.

Understanding this history of resistance is crucial for appreciating the complexity of the colonial experience in East Africa. It challenges narratives that portray colonized peoples as passive victims and highlights the active role that East Africans played in shaping their own histories. This legacy of resistance continues to inspire movements for social justice and cultural revitalization in East Africa today.

Role of Colonization in Shaping Nations, Economies, and Societies

The colonial era in East Africa, though relatively brief in the long sweep of the region’s history, left an indelible mark that continues to shape the political, economic, and social landscapes of modern East African nations. The legacy of colonization is complex and multifaceted, with both negative and positive aspects that continue to influence the region’s development and its place in the global community.

Formation of Modern East African Nations

One of the most visible and lasting legacies of colonization is the very shape of modern East African nations. The borders drawn by European powers, often with little regard for ethnic, linguistic, or cultural realities on the ground, became the boundaries of independent states. This artificial division has had profound implications for regional politics and stability.

Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania (formerly Tanganyika) emerged from British colonial territories, while Burundi and Rwanda were carved out of former German East Africa (administered by Belgium after World War I). These new nations inherited colonial administrative structures, legal systems, and languages, which formed the basis of their post-independence governance.

The process of nation-building in these newly independent states was significantly influenced by colonial legacies. Leaders had to grapple with uniting diverse ethnic groups within arbitrary borders while also dealing with the economic and social structures left behind by colonial rule. This challenge of forging national identities within colonial-era borders remains an ongoing process in many East African countries.

Moreover, the experience of anti-colonial struggle became a unifying narrative for many of these new nations. Leaders like Julius Nyerere in Tanzania and Jomo Kenyatta in Kenya drew on the shared experience of colonial resistance to foster a sense of national unity. However, this narrative often glossed over internal divisions that would later resurface in post-colonial politics.

Lasting Economic and Social Effects

The economic legacy of colonialism in East Africa is particularly profound and persistent. Colonial economic policies, designed to benefit European metropoles, restructured local economies in ways that continue to shape development trajectories today.

One key aspect of this economic legacy is the emphasis on primary commodity exports. Colonial administrations focused on developing cash crops and extractive industries for export, a pattern that many East African economies still struggle to diversify away from. This reliance on primary commodities has left these economies vulnerable to global price fluctuations and has hindered the development of robust manufacturing sectors.

The infrastructure developed during the colonial era, while extensive, was primarily designed to facilitate the export of raw materials and the import of manufactured goods. This outward-oriented infrastructure continues to influence trade patterns and economic development strategies in the region.

Land ownership and distribution remain contentious issues in many East African countries, directly stemming from colonial-era policies. In Kenya, for example, the dispossession of fertile highlands for white settler farms created land grievances that continue to fuel political tensions today.

Socially, the colonial period left a complex legacy of cultural change and social stratification. The introduction of Western education systems, while providing new opportunities, also led to the marginalization of indigenous knowledge systems. The predominance of European languages, particularly English, in education and administration continues to shape social mobility and cultural expression in the region.

The spread of Christianity during the colonial era significantly altered the religious landscape of East Africa. While many embraced Christianity, this shift also led to the erosion of some traditional cultural practices and belief systems. Today, the interaction between Christianity, Islam, and traditional African religions remains a dynamic aspect of East African societies.

Urbanization, accelerated during the colonial period, has continued to reshape social structures and cultural practices in East Africa. Cities like Nairobi, Kampala, and Dar es Salaam, originally developed as colonial administrative centers, have grown into major metropolitan areas, creating new social dynamics and challenges.

Post-colonial Challenges

Many of the challenges facing East African nations today can be traced, at least in part, to the legacy of colonialism. These challenges span political, economic, and social domains.

Politically, many East African countries have struggled with issues of governance and democracy. The centralized, authoritarian nature of colonial administration often set a precedent that some post-colonial leaders found difficult to break away from. Issues of corruption, ethnic politics, and lack of democratic accountability in some countries can be partly attributed to colonial-era governance structures and practices.

Economic challenges include the difficulty of diversifying economies away from primary commodity exports, addressing inequalities in land ownership and resource distribution, and developing infrastructure that serves internal development needs rather than just facilitating exports. The debt burdens of many East African countries can be traced back to loans taken on during the late colonial and early independence periods.

Social challenges include addressing inequalities in education and healthcare access, many of which have roots in colonial-era policies that favored certain regions or ethnic groups. The tension between modernization and traditional cultural practices, often framed in terms of “Western” versus “African” values, is another ongoing challenge with colonial roots.

Environmental issues also form part of the colonial legacy. Colonial-era practices of resource extraction and cash crop cultivation often led to environmental degradation that continues to affect the region today. Deforestation, soil erosion, and loss of biodiversity are ongoing challenges that can be traced back to colonial-era land use policies.

The artificial borders drawn during the colonial era have led to numerous conflicts and tensions between and within East African states. Border disputes, separatist movements, and ethnic conflicts often have roots in the arbitrary division of ethnic groups by colonial boundaries.

Understanding this colonial legacy is crucial for comprehending contemporary East Africa. It provides context for current political debates, economic strategies, and social issues. Moreover, recognizing this history is essential for developing effective solutions to the region’s challenges.

As East African nations continue to navigate their place in the global community, they do so against the backdrop of this complex colonial history. The ongoing process of addressing and transcending this legacy is a key part of the region’s journey towards sustainable development, social justice, and cultural renewal. While the colonial past cannot be changed, how it is understood and responded to will play a significant role in shaping East Africa’s future.